Murder at the Diggings: Part Three - Attention Focuses on Ah Lee and Lee Guy

Controversial reward notices prompt some voluntary statements leading to preliminary hearings into the guilt of Ah Lee and Lee Guy

Part Three of a multi-part series about the murder of Mary Young and what ensued afterwards. If you haven’t read the earlier posts in this series, you can catch up here:

Spotlight on the Chinese

As told in part two of this series, during the Inquest into the death of Mary Young, suspicion had fallen on the Chinese community. Initially, five local Chinese men were arrested - Chee Fong, Lew Ting, Ah Keen, and Ah Ting. On 10 August 1880, six days after Mary Young died, Ah Lee was arrested. All five men in custody were at the Coroner’s Court, for the final day of the Inquest on 11 August 1880.

Within the next few days after his arrest, Ah Lee and his belongings, particularly his trousers and his boots were examined. On 11 August, Doctor Thomas Bain Whitton noted scratches on Ah Lee's body and, on 13 August, the doctor examined blood found on Ah Lee's trousers. From this, the police began to mount a case against Ah Lee.

At this stage, the police weren’t sure of their case against him or whether or not there was anyone else they should be focusing on as well. Ah Keen had also been found to have scratches on him - two on the left side of his neck. The police had found teeth marks on Mary’s wrist but none of the five suspect’s teeth, including Ah Lee’s, matched the teeth marks found1.

Reward Notices (English and Chinese)

It was shortly after this, on 18 August 1880, that reward notices - an English version and a Chinese version were posted. Copies were posted in the Naseby gaol on the instruction of Inspector James Hickson of the Armed Constabulary, Clyde2. These were located in the hall of the gaol where the prisoners could read them.

Pardon for Accomplice Approved

The Reward Notice hung at Naseby gaol on 18 August 1880 was printed before the Governor had given his approval for a free pardon to be given. The Notice, therefore, said "the Governor has been advised to grant a Free Pardon to any accomplice". At this point there was only the promise of a possible pardon.

The Governor gave his approval for a pardon on 18 August 1880 and details of it were published by Notice in The New Zealand Gazette shortly after that:

"Notice - Whereas a widow woman of the name of Mary Young of Kyeburn, in the Provincial District of Otago, was on the Fourth instant found in a dying state and did subsequently die from injuries inflicted on her by some person or persons unknown Notice is hereby given that his Excellency the Governor will grant a pardon to any accomplice in such crime who shall give such information as shall lead to the conviction of the principal offender, or of anyone of such offenders if more than one"

Images of official papers relating to the reward and free pardon offered by the Government can be found here.

A Sixth Arrest

On the same day that the Reward Notice was posted in Naseby gaol, both Ah Lee and Ah Keen made voluntary statements. The next day, 19 August 1880, Ah Lee made a second statement which led to the arrest of Lee Guy. Lee Guy, you may recall, was Mary’s neighbour. He was the first to alert people that Mary had been injured.

Significantly, all of these statements were made after the Reward Notices had been hung in the gaol and after all the evidence found at the scene was public knowledge having been fully presented at the Inquest into Mary’s death.

The placement of the Notices in the gaol where the prisoners could see them was controversial. It was later argued by defence counsel that a statement on the promise of reward and pardon could unduly influence prisoners into making false statements. In addition, it was thought that the Chinese translation was misleading.

Voluntary Statements

The three voluntary statements, one from Ah Keen and two from Ah Lee, were made at Naseby gaol to Inspector Hickson through the interpreter Wong Ah Tack.

Ah Keen’s Statement - 4:30pm 18 August 1880

Ah Keen’s statement related to the pitchfork seen at Mary’s house on the day of her murder. The presence of it there was unusual and unexplained. The pitchfork belonged to Andrew Marshall, a coal carrier from Naseby. Andrew owned land about three hundred yards from, and opposite to, Mary’s house where he kept a stack of oats.

At the Inquest into Mary’s death, Sergeant Morton testified that he had observed the pitchfork stuck in the ground about three yards from the front of Mary’s house on the day of her murder. Hugh Marshall, Andrew’s son, said that, when he last saw the pitchfork prior to Mary’s murder, it was holding up a Tarpaulin at the stack of oats on his father’s land3.

Ah Keen in his sworn statement said:

“On Tuesday, thirteen days ago, the day before the murder of Mrs Young I saw Lee Guy go about half past 5 or 6 o’clock Tuesday night over to the stacks of oats in Marshall's paddock right opposite Mrs Young's, and take away the fork towards his house. He took it down the road towards his house. I did not see where he went, the fork had two prongs to it. I was knocked off work at the time. I saw no person with Lee Guy at the time”4.

Ah Lee’s Statement #1 - 7:00pm 18 August 1880

In this statement, Ah Lee said he had had a conversation with fellow prisoners Lew Ting and Chee Fong in the cells at Naseby gaol on 11 August 1880. Ah Lee relayed how, during that conversation, Lee Ting had admitted to killing Mary Young and Chee Fong had admitted to being there. Lee Ting had encouraged him (Ah Lee), to say that Lee Guy had murdered Mary Young. According to Inspector Hickson, prior to making the statement, Ah Lee had asked if he would be protected from his friends if he talked and was told he would be5.

When Ah Lee was asked by Inspector Hickson whether the other prisoners could have heard this conversation with Chee Fong and Lew Ting, Ah Lee said that he didn’t know whether Ah Ting heard or not. Ah Ting’s cell was opposite to his own but he didn’t have his head out his cell door during the conversation and so may, or may not, have heard. Ah Keen, on the other hand, had his head out through the door of his cell and must have heard the conversation. He was in the cell opposite Chee Fong and Lew Ting who were together in the one cell6.

Ah Lee’s Statement #2 - 5pm 19 August 1880

In his second statement, Ah Lee refuted his first statement from the previous day and implicated Lee Guy as the murderer of Mary Young. In so doing, he also implicated himself as being there and as aiding and abetting Lee Guy in the murder.

A handwritten record of all three statements can be read here.

And Then There Were Two

On the basis of Ah Lee’s second statement, the Police decided that they may finally be on the right track to solving the case. On 20 August 1880, Lee Guy was taken into custody. Ah Lee’s first statement was disregarded and Chee Fong, Lew Ting, Ah Keen, and Ah Ting were released.

At this point, the focus of the police was on building their case against Lee Guy and Ah Lee. No other leads were followed.

Ah Lee and Lee Guy in the Spotlight

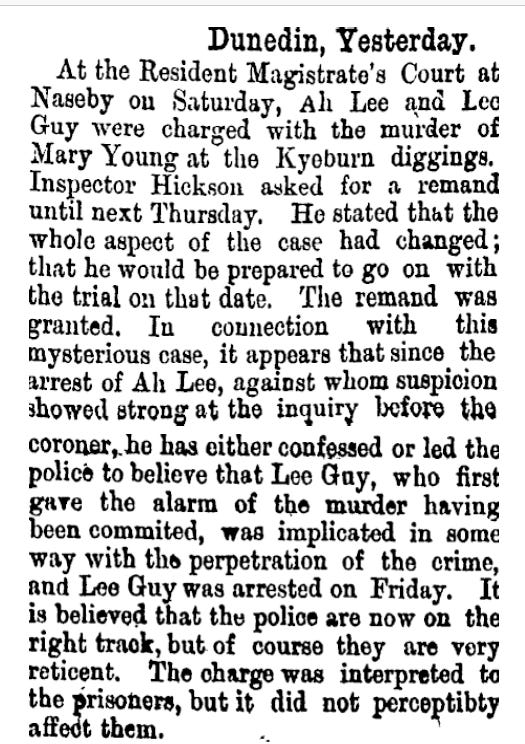

At the Resident Magistrate's Court in Naseby on 21 August 1880, Ah Lee and Lee Guy were formally charged with the murder of Mary Young and remanded in Custody pending a preliminary hearing into their guilt. This was reported in the Waikato Times on 24 August 18807:

Preliminary hearings were set up in Naseby to hear depositions from the various witnesses and to decide whether there was sufficient evidence to commit Ah Lee and/or Lee Guy to trial at the Supreme Court in Dunedin.

With regard to Lee Guy, I haven’t yet located information about what occurred at Lee Guy’s preliminary hearing but much of the evidence discussed there would have been similar to that presented previously at the Inquest and at Ah Lee’s preliminary hearing.

Ah Lee’s Preliminary Hearing

Ah Lee’s preliminary hearing was held in the Resident Magistrate's Court at Naseby on 26, 28 and 30 August 1880. It was presided over by H. W. Robinson Resident Magistrate, Naseby, and three lay magistrates. Mr Robinson had also served as Coroner at the Inquest.

Mr Weldon (Superintendent, Police Constabulary, Dunedin) appeared for the Prosecution. Mr Rowlatt (Defence Lawyer) represented Ah Lee. Details from the Hearing were reported in the Mount Ida Chronicle on 4 September 18808.

Much of the evidence about what occurred on the day of Mary’s murder, items found at the crime scene, and the arrest of Ah Lee would have been the same, or similar, to that already discussed at the Inquest. In addition, there was new evidence relating to the voluntary statements made.

What follows is drawn from papers relating to testimony given at the Inquest and what was reported in the Mt Ida Chronicle of 4 September 1880 about evidence produced, and testimony given, in Ah Lee’s preliminary hearing.

Voluntary Statements Admitted Into Evidence

Ah Lee’s defence lawyer, Mr Rowlatt objected to the statements made by Ah Lee being admitted into evidence at the Hearing. He argued that both statements had been given after the reward notices in English and Chinese had been posted in the gaol. He cited previous cases in which it had been shown that notices offering rewards and pardons, when seen by a prisoner, could unduly influence that prisoner into making false statements. He further pointed out that, not only were the reward notices (English and Chinese) hung in the gaol where the prisoners could see them, they were misleading, especially the Chinese version.

Mr Weldon countered Mr Rowlatt’s objection with an example of where such evidence had been allowed. He argued that the voluntary statements should be read at the preliminary hearing and the matter of admissibility left to the Supreme Court.

The Resident Magistrate ruled that the statements would be allowed because the majority of the Bench thought the evidence should be taken. However, he stressed that he didn’t wish it to be understood that this was his individual opinion. At this, Mr Rowlatt expressed surprise that the opinion of three lay magistrates was allowed to override that of a professional one. He also pointed out that one of the lay magistrates was the foreman of the jury at the Coroner's Inquest and had already made up his mind who the murderer is. He added that he felt he had a hostile Bench against him.

As a consequence of that ruling, both of Ah Lee’s statements were read in Court. It was the second statement that was particularly damning. It enabled the police and prosecution to pull various pieces of circumstantial evidence together and use them effectively against Ah Lee.

Ah Lee’s second statement (19 August 1880 - the day after the reward notices were posted in the gaol), read:

“The statement I made last night is not correct - every particular is not correct.

I saw Lee Guy murder Mrs Young. I went to Lee Guy's hut to have tea with him on Tuesday evening the night of the murder. I went to his hut about four (4) o'clock or a little after on the night of the murder. After tea, Lee Guy put on his boots and went outside of his hut. I waited inside until he came back at a late hour. I had no watch or clock and could not tell the time but it was very late about eleven or twelve o'clock.

When he came home he asked me to put on my boots and come out with him. We both came out of the hut together. When I went round Mrs Young's house to the front door I saw a fork sticking in the ground about five or six feet from the front door. Lee Guy said to me

'go to Mrs Young's garden and fetch three stones'. Then Lee Guy came with me and he carried two stones and I carried one. He carried the stones to Mrs Young's front door, then Lee Guy asked Mrs Young to open the door. She would not open it and Lee Guy took the stones and burst it open. When he burst the door open Lee Guy took hold of Mrs Young and threw her onto the floor, then he said to me'hold her legs down'then Lee Guy took one of the stones and threw it on Mrs Young. When he threw the stone down on Mrs Young I let go her legs and walked away.When I was walking out Lee Guy sung out to me -

'take hold of the fork and watch to see if anybody is coming. If you see anybody coming sing out’. I heard him searching and kicking up a row inside.Lee Guy was not in the house very long when he came out and asked me to come along to his hut. I went into his hut, we went in together then I asked him when he was searching did he find any money ! He replied

'no I could not find any'then I said to him' I don't believe you that you did not find any'then he took out his purse and showed it to me. There was money in it (notes and silver in it) I could not say how much there was a gold ring and a brooch in it, he showed it to me on the table. When he (Lee Guy) saw there was not much money in the purse he took it back to Mrs Young's. He said to me he thought there were three or four hundred pounds in the house, he said that when Mrs Young went to Hogburn [Naseby] he thought she went to the bank to draw money.Then I said to him

'now you have killed Mrs Young what are you going to do', he replied'I am not afraid'then he told me to go on to Hogburn.When he told me to go on to Hogburn I said

'What are you going to do'he replied"Tomorrow I'll go tell the Europeans that Mrs Young was murdered and they will not think it was I that murdered her'then I said'The Europeans will know it'then he said to me'If you don't tell I won't be afraid. If I go tell the Europeans that Mrs Young is murdered they will not think it was I done it’.Then I went straight on to Hogburn.Lee Guy fetched some string from his hut and was going to tie Mrs Young's hands with it he put on a mask before he went to Mrs Young's. Lee Guy had a bottle of ink in his pocket and it fell out where he took the stones from, he searched for it but could not find it. Lee Guy had two handkerchiefs, one was a white silk one, and the other was a white cotton one with a pink border to it. They were used one of them to stop Mrs Young's mouth with, the other one over her mouth.

Whilst in Lee Guy's hut I said to him

'why don't you take the handkerchiefs'And he replied'I don't want them they cannot be identified'Lee Guy tried to tie Mrs Young's hands with the string but could not do so, there he took up the stone and struck her”9

Through his questioning, Mr Rowlatt tried to establish that Ah Lee could have been misled into making a false statement. On cross-examination, Inspector Hickson said that immediately after the arrest of the prisoners, he gave instructions to the gaoler, Constable Nolan and to Sergeant Morton and Detective Henderson that they were not, in any way, to induce the prisoners to make any confession of their guilt and they must be particularly careful not to put any questions to the prisoners with respect to the charges against them. He said he renewed these instructions almost daily.

Notwithstanding this, Constable Nolan, the gaoler, deposed that on more than one occasion, he had invited Ah Lee into his office to warm himself at the office fire. He said that on one such occasion Ah Lee asked him about a bundle of clothes he had there. They belonged to Mary Young. He alleged that Ah Lee further elaborated on the contents of his second voluntary statement made the day before. The next day, in his office, there was a discussion with Ah Lee about a ‘looking glass’ and his eyebrow which he said he had shaved with a very sharp knife on the Sunday before he was arrested.

At some point during the proceedings, Mr Rowlatt, produced a literal translation of the Chinese version of the Reward Notice that he had managed to get hold of, presumably in an attempt to demonstrate the misleading nature of it. This read as follows:

"intent. Post Notice. Any same human being know it. Kyeburn Digging, murdered, one European woman, name Mary Young. Government put out reward. £IOO. Not matter any body know murderer —Pardon; Come to Court, tell ; pardon him. Then take reward money. That man not murderer, how many partner, never hurt deceased himself. Then receive reward ; also pardon. Hope soon come to Court, tell Inspector of Police. Catch murderer, have reward money paid. Intent. Post. Explain. Rest for ever! August 4, 1880, Murder. Wellington His Excellency the Governor. August 17th. 1880. Notice.”10

Wong Ah Tack, the interpreter, deposed that he never told Ah Lee that he thought he would soon get out of gaol and the only time he alluded to the reward was when interpreting the Reward Notice. As far as he could remember, he didn’t interpret the Reward Notice until after Ah Lee had made his first statement.

He further said that, when he did translate the poster to Ah Lee, he did so by interpreting what Inspector Hickson said when he read the English version of the poster. Wong Ah Tack said, he could not read the Chinese version himself. He had been born in Sydney and, had been to Hong Kong and to Canton twice. He had gone to school in in China for two to three months but could not read Chinese.

“Mr Hickson read it in English, and I interpreted it into Chinese I could not read the Chinese notice of the proclamation, It was written by Ah Fin, I have been informed. I can sign my name in Chinese and write the date … I only interpreted two statements for him. I am quite certain that it was after the first statement that I interpreted to him the proclamation of reward. I do not remember Ah Lee asking me any question before he made the first statement”. [Wong Ah Tack].

He said he interpreted the second statement to Ah Lee three times before Ah Lee signed his name to it, so that he would thoroughly understand it.

Blood Stains on Ah Lee’s Trousers

The second most significant piece of evidence was the blood stains that had been found on Ah Lee’s moleskin trousers.

Sergeant Morton deposed that, on arresting Ah Lee, he had examined his clothes. He was wearing a pair of old moleskin trousers which were very dirty, and appeared to be rubbed with clay about the knees. The pockets were cut out.

On 13 August he again examined the trousers, and found spots of blood on them:

“… two spots on each knee, and two small ones under the left knee. There was a patch on the knee, and the blood had pierced through the patch into the inner cloth. I pointed to it and said,

‘Blood John’ ‘Yes,’he said,‘Me killem sheep at Botting's yard, about 10 days ago ; blood got on them’.I handed them to Dr Whitton for examination” [Police Sergeant Morton]

In response to Ah Lee’s alleged reference to Botting’s yard, Garibaldi Botting was called by Mr Weldon. He said he had been a slaughterman at Botting's slaughter yard for the past twelve months up to the 20th August and he had never seen Ah Lee slaughtering at the yard.

Dr Whitton said he identified several blood stains on the knees of the trousers and below the knee on the left leg. In his opinion, the blood stains were from a mammal but not a sheep or a goat.

“I cannot say what animal, but they were not stains of the blood of a sheep or a goat”. [Doctor Thomas Bain Whitton].

Establishing Ah Lee was at Mary Young’s

Time of attack

According to the doctor’s testimony Mary had probably been attacked between 3am-4am on the morning of 4 October 188011. However, it may have been as early as 2am or even earlier.

William Parker deposed that when he got to Mary’s he noticed Mary’s eight-day pendulum clock had stopped. It had been working when he was in her house two days before her murder. He said, he remarked (sometime between 9:30 and 10am on the day of the murder) when he first noticed it had stopped that the breaking in of the house, had stopped the clock but didn’t think anyone heard him. He wasn’t absolutely sure of the time on the clock when it stopped:

“It was stopped about 2 o'clock, but it might have been a few minutes more or less. I am sure it was later than 12. I shook the clock, and then set it going. It went for a little while, and then stopped again” [William Charles Parker]

Whereabouts at Time of Attack

In Sergeant Morton’s deposition, he said that Jim Chan Yut had told him that Ah Lee sometimes went to his hut. He had slept there on the Sunday and Monday nights of 1st and 2nd August. He didn’t think he was there on the Tuesday night of 3 August (immediately before the murder in the early hours of 4th August). He did not see him when he went to bed, nor the next morning.

Mr Rowlatt asked when Jim Chan Hut would be in Court. He had been subpoenaed and Mr Rowlatt expected to cross-examine him. Mr Weldon said he had no intention of calling him because the police had experienced a lot of difficulty with Chinese witnesses giving evidence at the Hearing. He believed that there was collusion among the Chinese and those Chinese not implicated had thrown every possible obstacle in the way of the prosecution.

Mr Rowlatt accused the prosecution of playing tricks and slipping in hearsay evidence, which he would have objected to if he had not expected the witness to be called. He sought to have Sergeant Morton's evidence relating to his conversation with Jim Chan Yut, struck out. His request was declined.

Mr Weldon’s comments imply that a number of Chinese witnesses were actually called at the Hearing. Interestingly, I have been unable to find mention of their testimony in any of the newspaper articles I have found to date. Whether any spoke on behalf of Ah Lee at his preliminary hearing to establish his whereabouts, I don’t know. It seems that generally they were not believed, unless what they said favoured the prosecution’s case.

Scratches on Ah Lee’s Body

Much was made of the scratches on Ah Lee’s body but it was really only the voluntary statement that lent weight to the view that he got them during an attack on Mary. There was no evidence to prove that.

Sergeant Morton was the one who originally noticed the scratches on Ah Lee’s body and pointed them out to the doctor. He said he asked Ah Lee, before arresting him, how he got the scratches. At that time, Ah Lee said, he didn’t know how he got the scratches on his hands but the scratches on his face were done shaving.

Dr Whitton deposed that, when he saw Ah Lee on 11 August 1880 (seven days after the attack on Mary), the scratches on Ah Lee’s hands, right wrist, left forearm, right cheek, and right eyebrow were about six or seven days old. He thought there was nothing extraordinary about them, although the number of them might be thought to be extraordinary. Only two of them were more than half an inch in length and none exceeded sixteenth of an inch in width. There were no bruises, or nail marks or bites accompanying the scratches.

Joseph Pascoe, a draper from Naseby, said that Ah Lee did not have scratches on his hands on 2 August, two days before Mary was attacked.

Handkerchiefs

A white cotton handkerchief with a pink border was found under Mary’s body when she was moved by the doctor. A white silk handkerchief was also found at the scene. These were presumed to belong to her killer.

Joseph Pascoe, the Draper, deposed that he sold a white pocket handkerchief, with a pink border, exactly like the one produced in Court, to Ah Lee between 3rd and 6th May the previous year (1879). He remembered the date because Ah Lee paid him with a £1 cheque from Mrs McNamara which was dated 3 May and which he presented at the bank on the 6 May. He couldn’t remember the day of the week but it was between five and six in the evening. He remembered this time because the banks were closed when Ah Lee gave him the cheque. Mr Pascoe said he had only ever seen three handkerchiefs like the one produced and he wasn’t sure to whom he sold the other two.

I haven’t found any evidence to suggest this was disputed at the preliminary hearing but Ah Lee did later dispute Mr Pascoe’s recollection of events saying he had bought two white handkerchiefs from him on that day. In addition, at the Inquest, Alexander McHardy junior had said that he saw Ah Lee with a handkerchief like the one produced (white with a red border) at harvest time. That was before May when Ah Lee allegedly bought the handkerchief from Mr Pascoe.

Joseph also spoke about the time Ah Lee was living in a tent on his farm, six miles out of Naseby. This was between 27 August 1879 and 15 November 1879 when Ah Lee was doing some sod fencing for him. At the time, he was living alone in the tent. On visiting him there he had seen a white silk handkerchief and examined it taking it in his hands. He didn’t measure it but it was a similar pattern and material to the one produced in Court but he added: “I will not swear that this is the same one”.

Footprints at the Scene / Ah Lee’s Boots

At least two people were in Mary Young’s garden on the day after Mary’s murder looking for evidence. One was miner, John Brown. The other was miner, William Parker.

John Brown said he was near the garden fence at Mary’s when he saw footmarks on the east side of the garden, on the outside of the trench. He found a bottle of ink by one of the footprints and gave it to Inspector Hickson. The bottle of ink is one of the items referred to in Ah Lee’s second statement and, according to that statement, it belonged to Lee Guy.

William Parker said he saw footprints on the north east corner of the fence and tracked them around two side's of the fence. He pointed these out to Inspector Hickson.

According to a ground plan produced by Richard Henry Browne, an engineer from Naseby, the footprints were about seventy yards from Mary’s house and about thirty yards apart. He was unable to confirm that either of the marks was a perfect impression of the whole boot.

It appears that Mr Rowlatt tried to establish that the footprints could have been left by any number of people milling around on the day of Mary’s death. He questioned William Parker about people at the scene on the day of the murder. William Parker confirmed there were a lot of people around the house in the afternoon of the murder. He added that they were standing around the doors. He did not see any people in the garden.

Alexander McHardy Junior deposed that, at the time of Ah Lee’s arrest, when asked to put on his boots and go with Sergeant Morton, Ah Lee had put on some big newish looking boots. They were different to the elastic-sided boots that Alexander had seen Ah Lee with at Lee Guy’s hut some four weeks earlier. Those boots had a row of tacks up the centre. This prompted Alexander to ask Ah Lee about the elastic-sided boots he had seen him with earlier. Ah Lee said they were broken and lying under his bed. At Sergeant Morton’s request, Alexander returned to the hut where Ah Lee had been arrested and found the boots under Ah Lee’s bunk, all broken as Ah Lee had described. He handed them to William Parker who took them to the Police Station.

These were the boots produced in Court as evidence. Alexander confirmed that the ones in Court were the same as he had seen Ah Lee with earlier except that they had a hole in them. There was not a hole in the boots he saw four weeks prior to the arrest.

Mr Rowlett tried to establish that the boots were like hundreds of other elastic-sided boots. Alexander said he had only examined one of Ah Lee’s boots in Lee Guy’s hut. He had seen over hundred elasticised boots. He didn’t notice any peculiar marks about the boots except the row of tacks up the centre. He thought there were also tacks round the edge of the boots - he thought in two rows.

“I cannot swear that I have seen the same boot since, but I have seen one very much like it, at the hut where Ah Lee was staying at the bottom of Coal Pit Gully. I have seen the same boots to-day (produced)”. [Alexander McHardy Junior].

William Harvey, a bootmaker of Naseby had examined the footmarks and the boots for the police. He saw the footmarks on the 8 August, four days after the murder. He compared the marks and boots and thought they corresponded. The boots he examined were the ones produced in Court. He had concluded that they were size sevens. He said he looked at three impressions. One of the three showed that the boot had slipped so as to increase the breadth of the impression, but not the length.

Various other Items

Various other items found at the scene and mentioned in Ah Lee’s second statement were discussed. These are all items that had previously been mentioned at the Inquest and which Ah Lee would have been well aware of before he gave his statements. The only thing that tied Ah Lee to these items was his second voluntary statement.

These items included: the bottle of ink found by John Brown when examining footprints; a piece of string with blood on it found by William Parker while lifting Mary’s head to give her stimulants; a piece of calico with two holes in it and a piece of string rolled round it which appeared to be a mask, also found at the scene by William Parker; and stones from the garden.

William Parker identified the stones as coming from Mary’s garden. One stone, found in the house by William Parker, appeared to have been used to hit Mary. William Parker deposed that, prior to the day of the murder, the stone found in Mary’s house, and produced in Court, had been attached to a wire on the fence. He knew this because he put it there himself about 18 months ago with No 8 black fencing wire.

The Verdicts - Ah Lee and Lee Guy

At the conclusion of their preliminary hearings, both Ah Lee and Lee Guy were committed to trial for Murder at the next session of the Supreme Court, in Dunedin.

More about the Supreme Court Trial and its outcome in Part Four …

The information in this post is drawn from my one-place study - Kyeburn Diggings One-Place Study on the WeAre.xyz platform

As testified by him at a preliminary hearing against Ah Lee - Mount Ida Chronicle, Volume X, Issue 573, 4 September 1880, Page 2. Obtained from Papers Past [Website] - (accessed 2 February 2025).

Inquest, as reported in the Mt Ida Chronicle 12 August 1880. Obtained from Archives New Zealand by Jane Chapman (15 Jan 2025) - R20119946 1881 2014 Wellington Repository

Written record of statement obtained from Archives New Zealand by Jane Chapman (15 Jan 2025) - R20119946 1881 2014 Wellington Repository

Written record of statement - Archives New Zealand - R20119946. See Note 4

Report in Mount Ida Chronicle, Volume X, Issue 573, 4 September 1880, Page 2 via Papers Past (accessed 2 February 2025)

Waikato Times Volume XV, Issue 1272, page 2 via Papers Past (accessed 12 February 2025)

Mt Ida Chronicle - Volume X, Issue 573, 4 September 1880, Page 2 via Papers Past (accessed 2 February 2025)

Image of handwritten copy obtained from Archives New Zealand by Jane Chapman (15 Jan 2025) - R20119946 1881 2014 Wellington Repository.

Mt Ida Chronicle Volume X, Issue 573, 4 September 1880, Page 2 via Papers Past (accessed 2 February 2025)

He revised this in later testimony in the Supreme Court to 8-10 hours before 11:30pm - 11:30am-3:30am - Justice Department Papers transferred to Archives New Zealand in 1983 - Archives NZ - Item Code: R24386581 - Box number: 279 - Record number: 1880/4972

So much circumstantial evidence. Leaving not one, but two, handerchiefs at the scene doesn't seem like a wise decision if someone could identify them, as it appears someone did the one with the pink border. I wonder if the ink bottle really belonged to the murderer, whomever it was, or was just ordinary refuse from the house itself. Looking forward to Part 4!

My goodness. There’s a lot going on in that trial and I can imagine the language barrier didn’t help. Great super sleuthing Jane.